The Fed cut rates by another 50 bp (0.50%) yesterday for an unprecedented total 125 bp in just 8 days. This brings the target rate to 3.00%, already one of the lowest levels since Bretton Woods and the inception of the Dollar Hegemony era. And there is more to come: immediately after the FOMC announcement a major Wall Street firm predicted (begged?) that the next cut will be a full 100 bp to 2.00%.

By comparison, Fed funds were already at a low 3.00% on Sept. 1, 2001 towards the end of the previous recession, and Mr. Greenspan only took them lower because of the tragic events that transpired on 9/11. We may fault the Maestro for thus starting the largest real estate bubble in US history, but I am certain that every one of us would have reacted to the emergency in the same way and slashed rates, at the time.

Are we faced with an emergency today? Clearly, the unprecedented actions by the Fed and the administration show they are worried - panicked, even - that the developing economic slowdown portends much worse than a garden-variety recession. Their "sweat" is clearly showing, in sharp contrast to sensible advice ("Never let them see you sweat") and Shakespearean observation ("The lady doth protest too much, methinks").

I will try to briefly answer the three questions from the post title.

Why are they worried? Because the global economy has become so highly financialized that everyone looks to "markets" for their decisions - even their emotional well-being. Mainstream media run live tickers on their stations and sites, and economic news that were once relegated to the back sections are now at the front page. This is a very dangerous dynamic, nestled as it is within a highly complex system.

What are they worried about? That negative market action will be instantly transmitted via the above dynamic to the "real" economy, resulting in a seizure: slashed consumer spending and mass layoffs. And this holds for the entire world, not just the US, because global markets have become highly correlated.

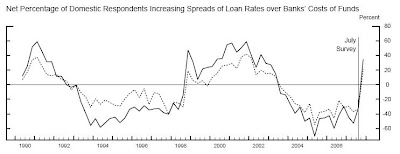

How fast could this happen? We already saw last week how quickly global markets can accelerate to the downside. In the era of "just-in-time" everything, the domino effects to the "real" global economy can't be cushioned by inventory builds or delayed production and delivery schedules. Every businessman is now trigger-happy - look at the chart below.

Perhaps the Fed's rapid-fire cuts will prevent the slowdown from turning into what Mr. Bernanke and the administration fear most. But their fear has me spooked, I'll tell you... To paraphrase FDR: The only thing I have to fear, is their fear itself.

_________________________________________________

P.S. The Monster Employment Index for January was just released, showing a sharp drop from previous months and also falling to the lowest level since February 2006. The index tracks online employment advertising.