After yesterday's post on American national debt and the value of the dollar, a reader asked to see debt/GDP ratios for other countries as well. Here is a table from the IMF (Int'l Monetary Fund) - click to enlarge.

Government Debt As % of GDP

Japan has the largest government debt in relation to its GDP and has been in this position for over a decade, as its government has fruitlessly attempted to revive a stagnant economy by spending public money on useless infrastructure projects, mostly roads and bridges to nowhere (what if they had spent it on "green" instead?). But then again, Japan's domestic savings readily finance this debt and the yen is not a global reserve currency. This should serve as a warning for our own policy makers, who continue to serve out red ink as if it were green beer at an Irish pub on St. Patrick's day.

The US government debt is projected to reach 97.5% of GDP at the end of 2010, the third largest in the G-20 after Japan and Italy (another perennial debt basket case, with the added twist of Mr. Berlusconi as Prime Minister). In absolute numbers the US has the largest debt in the world, of course.

Now, being the world's reserve currency perforce means that an adequate supply of dollars must be available globally to act as reserves and be used in pricing and trading various commodities. But how much is, in fact, needed for these functions? That's the multi-trillion dollar question, isn't it? Too little makes the dollar too dear and strangles the global economy, while too much makes it increasingly worthless, so people don't want to hold onto it, preferring hard assets instead ( including another, "harder" currency).

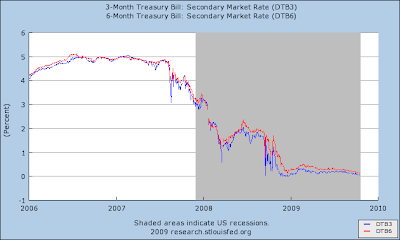

For quite some time now we have been flooding the world with too many dollars, first from the private sector in the form of mortgage, consumer and corporate debt and now as government bonds. To be sure, some of those Treasury bonds and bills are simply replacing private debt that defaulted on the books of banks and investors world-wide. That's what constitutes a financial sector bailout by the government: socializing private losses.

The battle of the dollar to keep its global reserve status may, therefore, be summarized thus: can US authorities regulate the amount of newly-issued debt so that it does not exceed by much what is currently defaulting? If the Great Recession keeps the flood of defaults going, then overall debt goes down through write-offs, the absolute number of dollars declines and the dollar becomes relatively more valuable. If, on the other hand, the economy stabilizes and starts to improve there are fewer defaults, more debt on the books and the value of the dollar declines.

This explains the inverse relationship between the value of the dollar in foreign exchange markets and prospects for the economy, as seen in stockmarkets and other risky investments such as junk bonds and second-rate mortgages. Stocks go up, the dollar goes down and vice versa.

It is a bit ironic and counter-intuitive: If the US economy starts tanking again, faster than the government can issue debt and induce domestic and foreign investors to buy it, then the dollar may strengthen - for a while anyway, until the nation's ability to service this debt ultimately comes into question.